Remembering my dad and how he showed his love

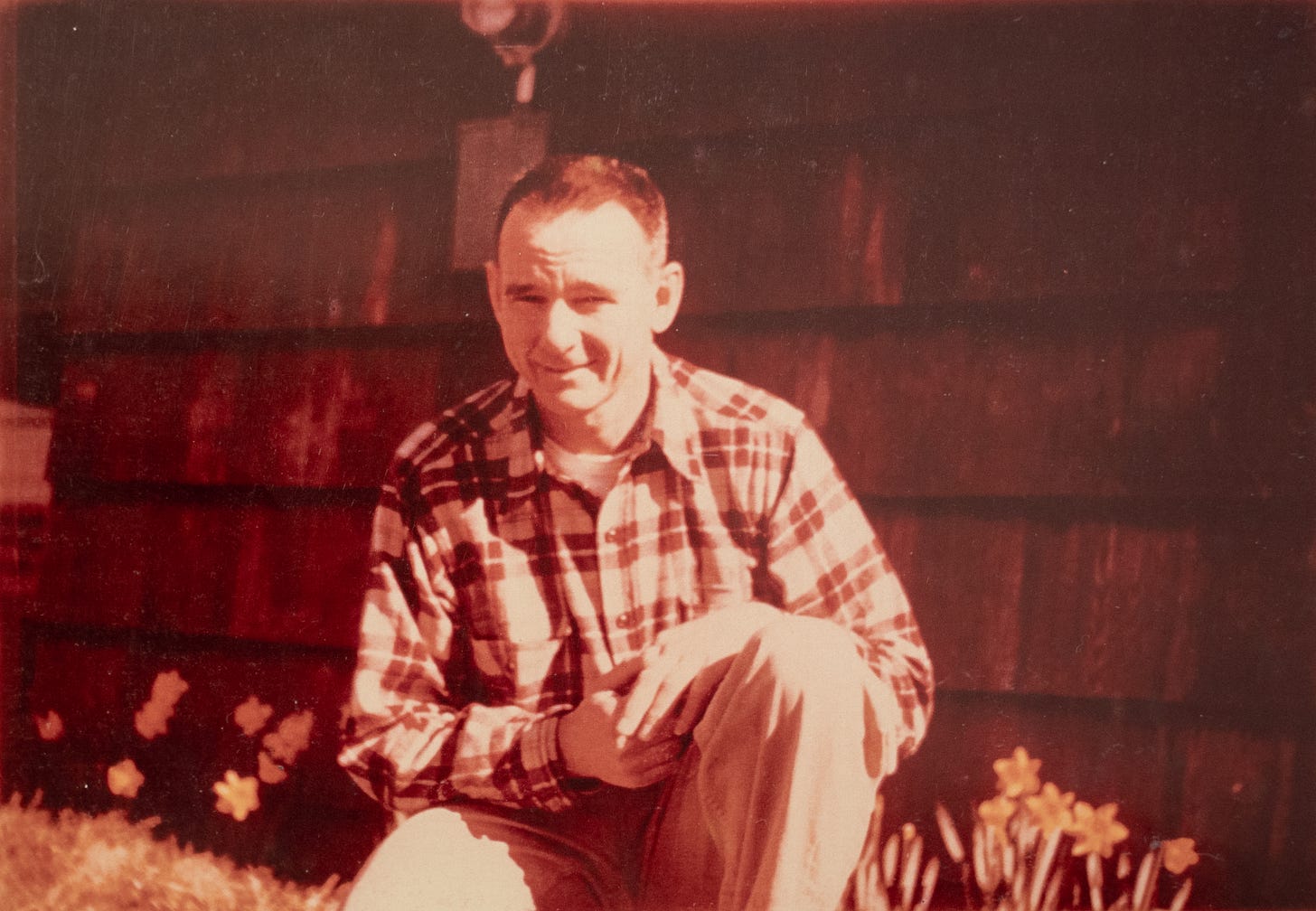

James J. Dunning (October 5, 1911 - December 8, 1987)

My dad died on this day in 1987. The following column was published in the Oregon Stater, the alumni magazine of Oregon State University, a school of which he was a proud alum.

I had to say goodbye to my best friend and my only hero Tuesday night.

My dad died from the complications of living, surrounded by those who loved him, his wife of 47 years, their five children and their three grandchildren.

He was 76.

This is a column I had hoped never to write, and yet I feel fortunate for the opportunity to talk about someone so very special to me.

I don’t intend to search for meanings that aren’t there or to try to make my father greater in death than he was in life, for he was truly an ordinary man with wonderful, simple goals. Like loving your wife and loving your kids and having everyone live happily ever after.

We were all blessed to be there when he died, but we were far more blessed to be there as he lived.

My earliest and fondest memories of Dad always involve the intense bond we formed while fiddling with the radio trying to pull in the football and basketball broadcasts from his alma mater, Oregon State.

It was always difficult to get the stations very clearly, but that seemed only to intensify the joy we took in sharing those hours together.

I remember on a Saturday in the fall he suggested we take a walk over to the UC Davis campus instead of listening to the game, and I was surprised that the game I had been looking forward to so much didn’t seem so important to him.

But I went along instead of staying home, because listening to the game without him would be like not listening to it at all. And besides, he had a strange twinkle in his eye as we left on our brief journey.

As it turns out, Dad had found that there was a TV - something that we didn’t have - in a recreation lounge on campus, and better yet, it was one of those almost-never occurrences when the game of the week included Oregon State as one of the participants. To listen on the radio was one thing, but to actually see them run up and down the field on a television screen was beyond my wildest dreams.

What I’d give to be 6 years old again, holding his strong hand, looking up to him and smiling as our eyes met, knowing he always had something special like that in mind for me.

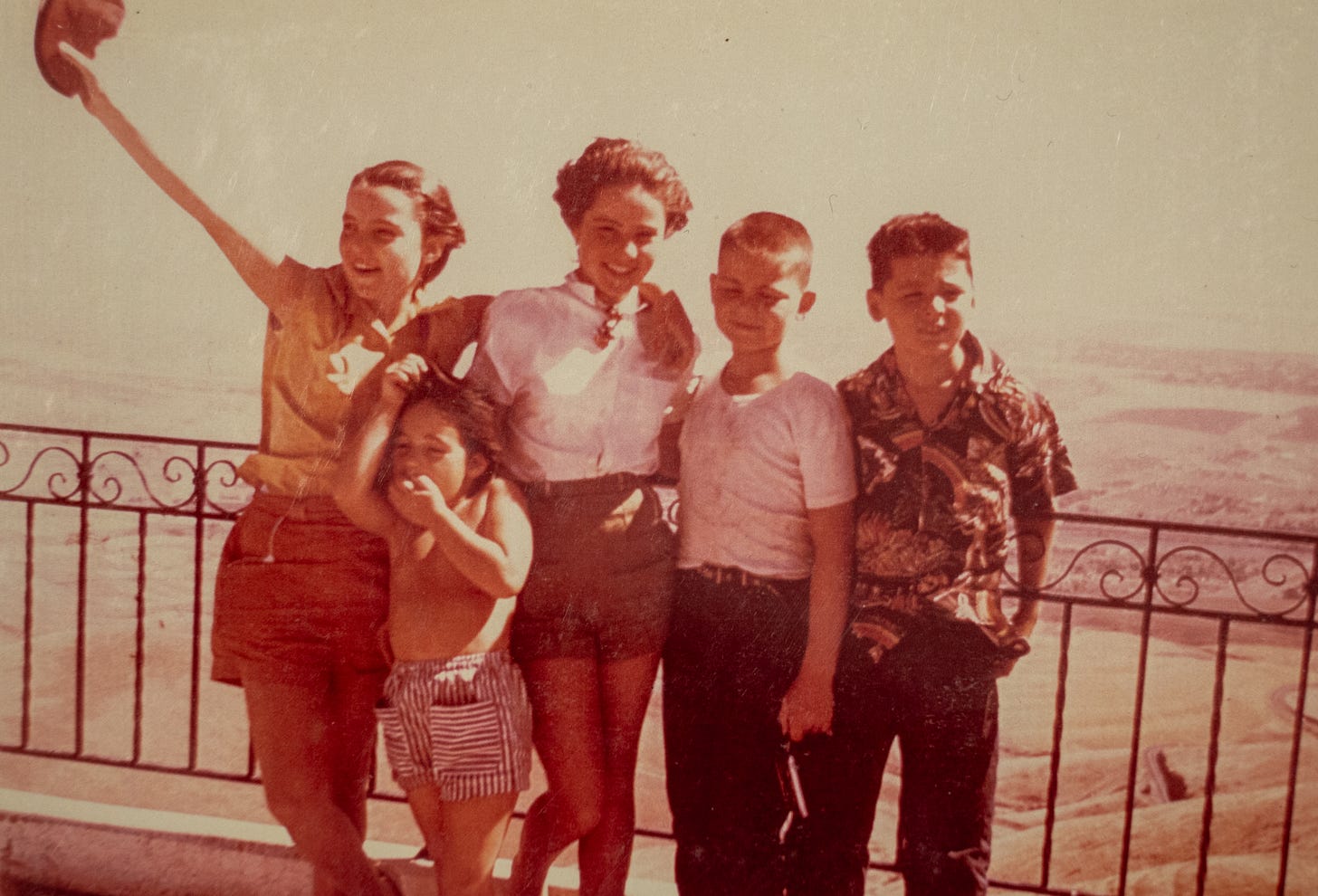

But Dad made all five of his kids feel that way as they were growing up. As I wrote one time on his birthday, he especially relished being able to surprise us on birthdays and Christmas in ways we never could have imagined.

Not with gifts born of money, but of a thoughtfulness and imagination that showed how much he loved us.

I remember the rides in the country between here and Woodland where he’d offer a nickel to the first one to spot a pheasant.

But because my youngest sister was at a distinct age disadvantage, not to mention being too short to get a good look at the road, she and only she got a nickel just for seeing a lousy magpie.

It was the only time in my life I felt my father was being unfair.

Dad’s impact on my emotions was such that on those rare occasions when I let my heart wander far enough down the road to the day I would be grown up, I imagined myself only as a father, with dozens of children and an endless string of Monopoly games, Hershey Bars and backyard football games.

I remember when we were little Dad used to check on us late at night by coming in and watching our chests move up and down under the covers. If we were still awake, my brother and I would hold our breath as long as we could. Fortunately, my children never learned that trick, though their father checks in on them the same way every night.

There must have been some bad times, but I don’t remember them now.

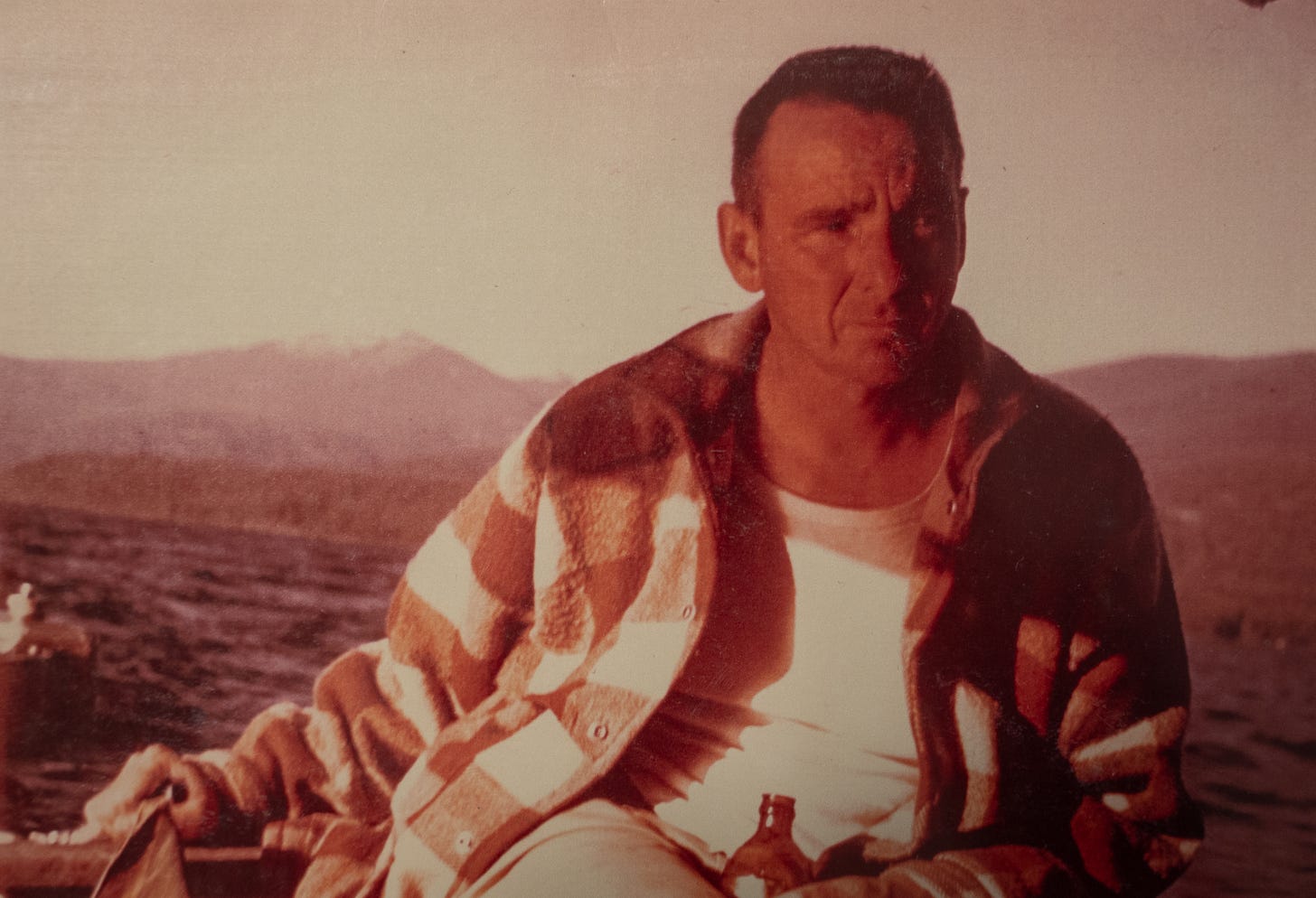

The memories I’ll carry forever of my dad, however, are not childhood ones, but rather those of his later days.

For the last 10 years, Dad’s body was ravaged by the progressive debilitation of Parkinson’s disease, but he showed us every day that the condition of the body is a mere distraction for those rich in spirit.

As the disease slowly and steadily robbed him of one function after another, he never lost his ability to laugh and tease, even as his ability to speak waned.

And especially, he never lost that sparkle in his eyes, the same sparkle I had seen so many years before while walking with him to campus to view that rare television set.

And he never lost his love for the woman he married and the five children they shared.

On her birthday a few months ago, he wanted to get her some gladiolus, her favorite flower.

He could barely walk - and not at all without assistance - and it would have been much easier for him to just have one of us call the florist or pick them up for him on our own.

I was the lucky one who happened to be around that day and he asked if I wouldn’t mind walking with him to the florist so he could pick out the flowers himself.

And so we did.

I remember when we were kids how we’d always pretend to be asleep, whether we were in the car or on the couch, so that Dad would carry us off to bed.

It wasn’t the carry that mattered, it was just that feeling of closeness you got from being in his arms and having your head pressed up against his heart.

And how ironic that many times in these final few months so many years later, when Dad’s bedtime had come, my brother and I had the distinct pleasure of returning the favor.

I once had someone tell me that it was too bad my dad was so debilitated that he just couldn’t be like his old self, but it didn’t register. I liked his new self just fine.

And so did my mother, who cared for him night and day for so many years, not out of duty or guilt or pride, but out of pure and simple love.

As Dad lay dying, Mom told him through her tears how much she loved him, but assured him that God loved him even more.

All I can say, God, is you have a tough act to follow.

So long, Papa.

Until we meet again, I’ll just have to root for Oregon State alone.

Reach me at bobdunning@thewaryone.com

beautiful writing pod. hits extra hard this year and you will never root for oregon state alone, go beavs

I would pretend to be asleep so my dad would carry me inside from the car. That trick must run in the genes.